BACK AND BETTER THAN EVER

With an essay in The Iowa Review!

I am back, friends, after a lengthy summer hiatus in which I was writing the book and being a parent and trying my best to, as the kids say, touch grass from time to time.

As I write I find myself compelled to listen to Jane’s Addiction’s 1988 record Nothing’s Shocking (which I do not believe we own on vinyl) because for some reason it breaks my heart not so much that Perry Ferrell punched Dave Navarro or that he’s a mess or whatever (because, duh) but somehow that this all went down during the song “Ocean Size.” That song more than any other encapsulates for me Ferrell’s lost boy persona, his childish desire to be as “big as the ocean, no talking and all action.” That infantile longing to be indestructible, untouchable, inscrutable. As Peter texted me this morning, ‘hedonism does not lead to personal growth” and yeah, amen to that. Anyway my thing with Jane’s Addiction was like an intense three months in my freshman year of college lest you think I was somehow frequenting the seedier side of Los Angeles circa 1986, which I most certainly was not, but it does underline a thought that I hope to flesh out at a later date which is that the 90s, the early to mid-nineties, anyway, were so inextricably about the eighties that their signature feeling was of having come too late to a really amazing party. Even so, I’m glad to be approaching fifty rather than sixty; if I were sixty-five, like good old Perry né Bernstein, I’d sure be wishing I’d partied just a little less hard.

But I digress. Perry’s moved on to singing about how sex is violence and the Andrea Dworkin 80s are swaying along but I’ve lost interest.

This month I have an essay in The Iowa Review, which is unironically a bucket list thing for me. Some of you might know that I got my MFA in Creative Nonfiction at the University of Iowa, a program which was very much not The Workshop but instead Workshop adjacent in a way that felt both insulting and subversive. It felt right, is what I’m saying, to the mentality I carried with me out of my nineties, to be the ugly stepsister of the most popular kids on the creative market— but that doesn’t mean it felt particularly good in practice. Nevertheless, my experience at Iowa formed the basis of what I think of as my creative practice even as I moved into academic writing, because as my mentor John Peters always said (teaching at the same institution), academics are essayists, too. And The Iowa Review was sort of the pinnacle of what I thought of as creative recognition from worthy peers. Like many graduate students in the MFA programs, I read slush manuscripts for TIR, and I watched in awe as the august editor, David Hamilton, carefully weighed in on every one. If TIR was the distilled essence of literary excellence, David was its personification: slow and measured in speech, deeply midwestern, keenly suspicious of a snap judgement or a flip comment.1 This was so different from the performative, even spectacular academic jockeying2 to which I’d been exposed at the University of Chicago, and it baffled me as much as it enticed me. My academic mentors in Chicago thought of creative writing as itself glib, yet here was their primary gatekeeper weighing his every word, and demanding of every word on the page that it matter, too— but not because of its fireworks, because of its unassuming weight, its naturalized inevitability.

Now might be a good place to say that the central conceit of the Iowa writing program when I was there could be summarized as “naturalized inevitability”— there was a sense that “good writing” sprang fully formed out of the breast of the American prairie without any influence, reflection, or unwholesome ornament. In fiction, plain spoken naturalism was the dominant mode— leave that showy experimentalism to the coasts. In nonfiction, we were taught to idealize texts like James Galvin’s The Meadow, a similarly minimalist document of place made delectable— again in true Iowa style3— by its proximity to the incandescent fame of Jorie Graham, the ethereal poet who was Galvin’s ex and who had recently left for Harvard. When I say “naturalized,” then, I do mean a certain ideological smoothness around the notion of talent and of insight, such that what came out of the Workshop was ratified already as literary, full stop, without any recognition of style or market. Just good plain writing, instead of a particular choice about what was not only laudable but what was saleable.

This was a strange environment to navigate for a twenty-five year old with no life story yet to tell; stranger still because my formative years had been so deeply influenced by the notion of the avant-garde, by the de-facto virtue of inscrutability, by the mandate to appear naked without vulnerability. At Iowa I found neither nakedness nor vulnerability. I found a kind of hands-spread, simple gesture of here, here it is, I can show you. Never telling, always showing. No manifestoes, only keenly observed details.

My time volunteering for The Iowa Review left me convinced that at least someplace in this world there were grown-up people who took writing seriously. Who were careful in a way that I hadn’t yet fully taken into account. And so in the back of my mind, The Iowa Review was the place you went for a fair shake, for an honest evaluation apart from the whims of the market. Imagine my delight and my surprise, then, when they consented to publish the essay I’d sent them. I’m not sure I can quite put it into words— especially given my tendency towards glibness. It’s a big deal to me, y’all. A big fucking deal.

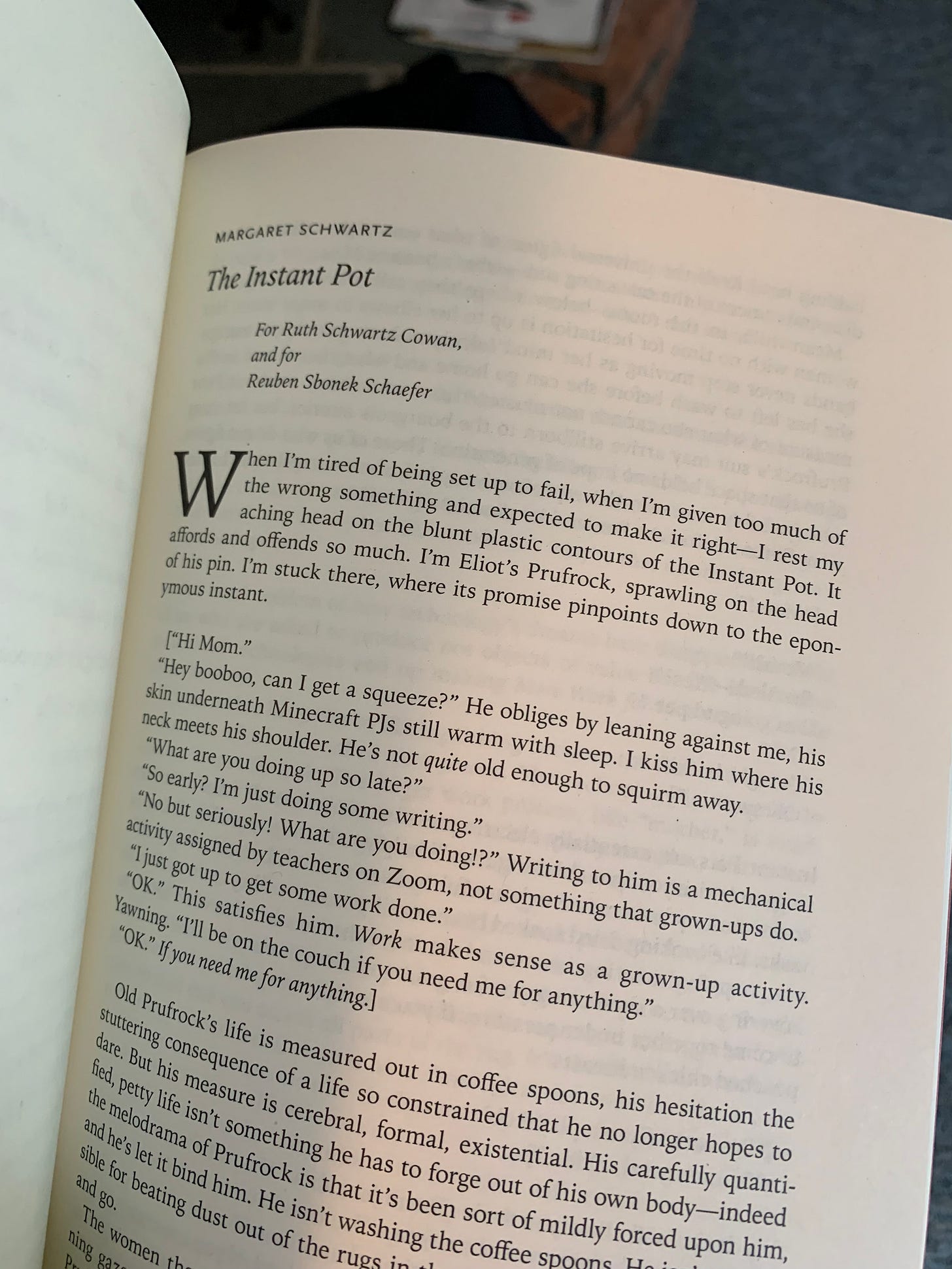

The essay is about the Instant Pot, and also somehow about T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock,” a poem I loved when I was sixteen. It’s also about trying to write in the very early morning of a gray November, when seven-year-old Reuben gets up and finds me and interrupts all my already-jangled streams of thought with the burbles and chirps of his inimitable existence. That relation, that tension, is at the heart of the essay— the pull towards a loved one and the push away into the life of the mind, and the envy and rage of someone like Eliot’s Prufrock, who thinks himself a Hamlet of the drawing room because he’s awash in his own interiority. What a refuge, and a privilege, that interiority; yet how delightful, the weight of this small boy in his still sleep-warm pyjamas, pressing into my side.

The essay can be found in the Spring 2024 issue of The Iowa Review.

It will surprise no one to know that I was then as I am now full of snap judgements and flip comments, but David tolerated me with the same gentle equanimity that he gave to everyone around him.

For example, I once watched the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins pick a fight with Bruno Latour during the latter’s invited public talk, which culminated in him flouncing out of the room with all of his graduate students in tow. Stunning theater!

Boy oh boy do they love their gossip. It’s a small town, after all, and half the full-time inhabitants are writers!

Amazing!! Ordered a copy! Congrats. And I did not know you got your MFA in nonfiction at Iowa. Had no idea. Another great substack post.