A Technics of the Unobtrusive

containment and its discontents

Greetings from the dregs of February,1 the month where I usually start to get sick, hate my job, and question my life choices. Not necessarily in that order. When you work in academia, you sort of sprint through these really tough bits (midterms plus advising plus conference submission deadlines plus kids out of school, in the case of February)— where you have very little control over your time because it’s all super regimented by the demands on it, and then there are these other bits where you’re mostly “off” and you are at nearly total liberty to structure your time but there’s all this like, looming shit that you aren’t sure how to shovel through because the previous six months have taught you NOTHING about time management since you’ve just been chasing one deadline after another like a hamster on a wheel.

Which is why I want to scream when a civilian says to me, “you are so lucky, you get summers off!”

Of course it is in many, nontrivial ways LUCKY and I’m very grateful to be employed #inthesetryingtimes and I’m sorry in advance for whining but I just unearthed a steroid inhaler prescribed last year at this time that thankfully wasn’t expired because what started as just some annoying post-nasal drip has settled in my chest which means I’m feeling sort of tubercular and fragile. If this were a Dostoevsky novel I’d be the consumptive with hectic spots on her cheeks and a feverish stare, but it’s not so I’m in my sweatpants and one of those drapey shawl type sweaters that I somehow acquired as soon as I turned 45. It hides a lot of flaws.

What I’ve been thinking about in my free time (ahem) this past month is container technologies. Specifically, Zoë Sofia’s “Container Technologies”, an article written in Hypatia in the year 2000 (I always hear that phrase sung in a high, eerie tone as in a 1997 Conan O’Brian sketch), long before I was a media scholar or a mother.2 I’m thinking about the article because what bugs me about it is how often it’s cited, but how infrequently anyone actually uses it, or engages with its content. It gets cited as a reminder that technology a) is gendered and b) has qualities that aren’t the typical macho stuff like destroying space and time, building and smashing things, and so on. Technology can be as warm and fuzzy as a jug holding warm milk. Or a fermentation vat, unobtrusively making beer. Or, as Sofia remarks almost casually, as a womb.

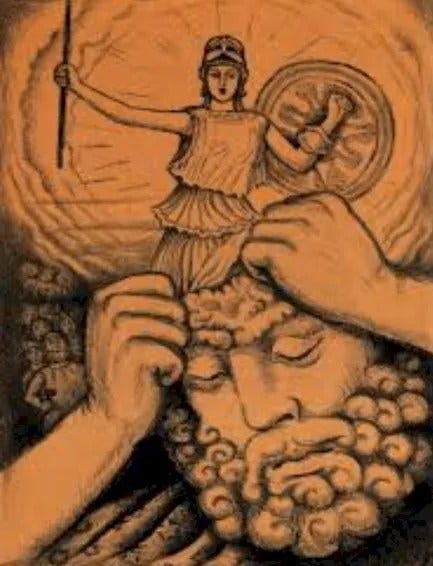

Which brings me to the second reason why I’m interested in the article. I’m trying to figure out what I’m doing in this second book. I talked last month about my first book, about corpses, and how in the end I was trying to cope with my father’s death by writing the book. The why of writing is obscured in academic prose, which must appear self-contained (containment! oooh!) and confident, springing like Athena fully armored from the split skull of knowledge. But it isn’t that way, of course, and if I try to dive into that voice without figuring out where I’m headed, it just ends up with a lot of inchoate howling, in my case about babies and Instant Pots and that kind of trembling, barely-holding-it-together feeling that in my mind is best exemplified by the surface tension on an overfull glass of water. What gives?

What gives, indeed. I’m so full of exhaustion and rage that I struggle to understand what I’m trying to express except some sort of barbaric YAWP of despair. I’m trying to cope with that double whammy I mentioned above: becoming a mother and a professional at the same time, with all the disillusionment that entails. And there’s plenty of it to find! Women, mothers, are under tremendous pressure— mostly much worse than I am. Black women are dying in childbirth at rates that should shock the so-called developed world. A woman in Michigan was convicted of manslaughter because she failed to stop her son from executing a deadly school shooting, giving new meaning to the scope of maternal guilt. American families routinely spend twenty percent of their salaries on childcare. The homes of some of these families are populated with women who have left children in places like Barbados or the Phillipines to care for these white children (whose parents, despite their privilege, cannot stop working to care for them), and everybody acts like this is somehow a fair exchange of goods and services on the free market. Someone tried to sell me “leak proof” underwear based on the premise that my statistically likely postpartum incontinence3 might be best solved not by access to adequate toileting or medical research but by a pair of $35 underwear— and sweetened the deal by claiming to donate a portion of the proceeds to get fistula surgery for African women. This is also billed as a totally normal way to solve problems associated with being in a childbearing body, the best possible fix when something like, I don’t know, an actual material benefit from taking the furthering of the species into your own body might be appropriate.

So what might it gain me to think systematically, analytically— dispassionately!?— about wombs as container technologies?

I must admit that the relatively novel application of the term “technology” to my, er, lady bits, flatters the part of me that wants to be in on like, important, cutting-edge stuff. Gestation and its outcomes— specifically but not necessarily childbirth— are shrouded in the kind of naturalized mystique that in my case added to the trauma of actually experiencing them. There is nothing natural or easy about carrying or giving birth to a child. As Sophie Lewis quips in her excellent screed Full Surrogacy Now, “it’s a wonder we even let fetuses inside us.” According to the biologist Susanne Sadedin, the specifics of our placenta make gestation especially risky for humans, compared with other mammals. Though all gestational cells, regardless of species, “rampage” through the body and are, for this reason, also linked in the research with the unchecked growth of cancerous tumors, only the human placenta invades the body to such a degree that its removal can result in a lethal hemorrhage. Other mammals, when an embryo fails for whatever reason to thrive, will simply absorb the necrotic tissue back into their body’s metabolism, where it is processed much like any other sloughing of dead cells. Not so for the human, whose placenta has “breached the walls of the womb” such that its implication, both hormonal and physiological, in the broader arterial system of the body makes its extrication quite literally a bloodbath. This biological specific— which Lewis dubs a “ghastly fluke”— determines the painful, traumatic and very much not easeful experience of miscarriage, abortion, and still birth for human beings.

So if “technology” is flattering in the sense that it seems to point to some kind of important work going on rather than a mystified “tender expectancy,”4 it does not quite seem to capture the nightmarish quality that, it appears, the (bad) luck of the evolutionary draw has bestowed upon the human womb. It brings to mind nothing so much as the cruel joke of most of female biological functioning: if women had been designing this technology, they’d have made it much safer and less painful! On this point, Sofia does not weigh in, but Lewis does: “This situation is social, not simply ‘natural,’” she writes. “Things are like this for political and economic reasons: we made them that way.”

But we didn’t, quite, did we? The response to the specifics of human biology is certainly social, political, economic. The fact that, for example, IVF clinics are being sued for wrongful death is not a “natural” consequence of our biology. But the difficulty human fetuses present both when being implanted in and extracted from their hosts? This is a feature of our embodiment.

And here is where Sofia soothes me, because the remarkable thing about her essay is its ability to hold both the cultural configuration of the container and its material characteristics. So much of social theory insists on an either/or– either it’s culture all the way down or you are a positivist, an enlightenment thinker clinging to an unproblematized notion of an observable, objective reality. My wording here betrays my own intellectual “upbringing”— and indeed, Sofia is writing in a moment when the cultural constructionist backlash against the enlightenment positivists was at its height. As someone who came of age academically in the nineties and early 2000s, I was taught a social constructionist critique of science, for example, was nearly orthodoxy.5 To seek either philosophically or politically for an unconstructed, ‘natural’ or ‘essential’ quality of a phenomenon or thing was reactionary. Poststructuralism– far from being the apolitical navel gazing its critics decried– laid out precisely the stakes: ethnocentrism, sexism, imperialism, racism. Luce Irigaray, whom Sofia cites in this essay, was part of that body of literature, and in citing her, Sofia indicates that its stakes are hers as well. So why also make a move to consider the material nature of the “objects and spaces themselves”? And what does that have to do with the complex experience of giving birth in our particular historical moment?

Now, as I mentioned, Sofia doesn’t dwell on the womb as a container technology, but she invokes it to illustrate the way that containment as a mode of technological mediation is associated with the feminine. “Like noisy and disruptive boys in class,” she writes, “aggressive tools and dynamic machines capture more attention than the quietly receptive and transformative ‘feminine’ elements of container technologies” (185). Holding— and more than that, being made to hold, being designed for containment— is itself a “technics of the unobtrusive.” A theorist of container technologies must, then, “work against the grain of the objects and spaces themselves– not to mention the ingrained social habit of taking for granted mum’s space-maintaining labors– to bring to the foreground that which is designed to be in the background” (188).

I would like very much to bring into the foreground certain things which have been designed to be in the background. The labor of gestation and childbirth is one of them. But the only way in which one could construe that technology as “designed to be in the background” is if one understands evolutionary biology as intelligent design— and I’m not ready to get that theological. If the womb is a kind of avatar, after which other kinds of transformative containment (fermentation vats, supply chains, tea kettles) are modeled, then where does the unobtrusiveness come from? Does it come from a misunderstanding of the nature of gestation— a chauvinist prejudice, born (ha) of inexperience with its violence, fear, and trauma? Or is there something itself deeply interior about the experience of pregnancy, something that makes it hard to pin down on what Luce Irigaray would call a “grid of intelligibility”? Is it culture all the way down, or is there something in the nature of gestation that requires a technics of the unobtrusive? Let me try to explain with an example.

When I first became pregnant, I felt no inkling of the presence of any person within me, let alone kinship with them. What I did feel was violently, overwhelmingly, and constantly unwell. The doctor reassured me that most symptoms would likely subside around ten to twelve weeks. I could not imagine feeling as I felt for another twelve seconds. I kept looking around in bewilderment, as if having found myself pregnant I would be evacuated, perhaps by helicopter, to some setting more amenable to my extreme condition than, you know, ordinary life— to which the doctor returned me with a cheerful admonishment to buck up and, you know, suffer the curse of Eve like a good girl.

I barfed and I cried and I laid down and tried to sleep, only to stumble to the toilet again for another round. I threw up bile in the middle of the night and crackers in the midmorning and whatever random thing my cravings had compelled me to consume in the afternoon. The only respite I felt— which did feel sort of appropriately uterine— was when I was immersed in water. Peter (the coauthor of my condition) would hold me on my back in the water and together we would gently sway, while I salted the chlorinated waters with my tears of relief.

Shortly after I became pregnant (fell ill), the city in which I lived was flooded. But unlike Noah’s flood, the waters didn’t come from the sky. There was no single precipitating weather event, just that there had been a very snowy winter. Upstream and to the north, the mountain snows melted, and the streams ran into one another, swelling and swelling the Iowa River until it overflowed its banks. We watched it come in slow motion. One morning we turned a corner and the river was just there, where the street should have been.

One morning I was ill, and the next I was pregnant. Before ultrasounds and measuring of nuchal folds and chorionic sampling, there was what was called the “quickening.” A fetus was said to be quick when you (the pregnant person) felt it moving. This happens around sixteen to twenty weeks of pregnancy, which itself corresponds with a significant drop in the chances of fetal death or miscarriage. Even in the early twenty-first century, when I first became pregnant, midwives and obstetricians encouraged expectant people to pay attention to fetal movement— if it slowed or seemed to stop, this could be cause for alarm. It is in this sense the first communication you get from the person inside you— if you know how to read it.

But I didn’t know how to read it. I thought it was gas. That funny, bubbly, silverfish sort of squiggle. Definitely aquatic, hardly vertebrate. The doctor asked, “have you felt the baby move?” And I immediately said no, and then thought of those funny little silverfish squiggles. Could it, could they— be burbling: “Here I am!”? The child, turning and wriggling according to its own, inchoate rhythms. “Here I am!”— “I am not you.” The first traces of separation, thus communication, delivered in the medium of the flesh.

Communication of this kind gives new meaning to the word private. I was not communicating with myself, strictly speaking, but much like pain, this kind of experience stretches descriptive language to its limits. If you have felt this feeling, you know what I’m talking about, but your probably have your own set of metaphors. The image that comes to my mind is silverfish— or perhaps quicksilver. Something feral and spontaneous and serpentine, something fleet, mobile, flashing, quick.

Is this a technics of the unobtrusive? Trying to find the language to feature it for you?

Sofia’s technics of the unobtrusive consists of a list of her household objects, room by room, and a short description of their containing qualities. My first attempt at a technics of the unobtrusive was the description above of the feeling of pregnancy— the embodied, physical experience of something that is overdetermined by its cultural mystique. It is easy to read backwards, and call that period of illness in the first trimester the experience of invasion, of being overcome— and to call the quick womb the first site of human communication. In both cases I was a container, but in the first I was more like a fortress overrun by an invading army. In the second, I was like the water in which the whale blows its bubbles and sends its sonar clicks: the medium and the reception all in one, for nobody could sense it but me.

Later, I would watch my belly bulge and shift, unbidden, in public. There would be definable shapes stamped into my skin: darling buttcheeks and sharp elbows and tiny feet. Someone else (Peter, for example—or, you know, and overly friendly stranger, because that happens too) could feel it, and know it for what it was. But even then I could only give Peter his own experience of feeling from the outside. I could only ever give the ultrasound technician or the midwife a numerical estimate of how often the baby moved in an hour. No one wanted to know, nor could I quite express, the bone grinding slipperiness of the movement inside me. The way she wiggled when I drank a Diet Coke, or stilled, seemingly lulled, when I slipped into the waters of the pool. Or whether I was just mapping those narratives on to her inchoate, biological squirming.

So I think where I’m ending up is that a technics of the unobtrusive has something to do with communication, and privacy, and embodiment. I paid attention to my status as an active container: a person working with literally all her might to construct another human where there had been no one. It is work, and just as containment itself is active, so too gestation is made up of a billion tiny acts of facilitation and forbearance. But these acts resist representation, they slip through the nets we weave to catch meaning. And it may be that this is their nature.

A feminist media studies, then, refuses to let that nature be destiny.

Because, yes, what I want is a feminist media studies. I began this essay— well, ok, I began this essay by complaining about February and being sick, but after that I noted that not many scholars do more than cite Zoë Sofia’s “Container Technologies.” I wanted to know what kind of scholarly practice one could build on its foundation.

Sofia is beautifully adept at what Walter Benjamin called thinking in constellations, or the nonlinear arrangement of points to create an entirely unique image. The best way to illustrate this for those who haven’t read the article is to talk about the eclectic group of thinkers Sofia calls upon to build her article: the child psychologist Winnicott rubs shoulders with media historian Mumford and cyberneticist Batson. She takes a little bit from each of them and arranges it, like a mosaic,6 to create a different image.

Constellation thinking is an interpretive procedure that “draws attention to the unstable conditions” of interpretation itself.7 In this way it is, I would argue, inherently feminist. There is no archemedian point8 from which the constellation thinker makes her observations. There is no hierarchy of being in the constellation, but rather an assemblage of points in a field. She stands situated in her own body, in her own mind, and her own experience. From there she casts her mind’s eye into the sky and describes the patterns it traces. The claim to truth thus subverts the patriarchal, reason-and-hierarchy-obsessed Enlightenment model of knowledge. It also thwarts any attempt at ideological universality– it states itself as situated, and as such historical. And yet it still theorizes– that is, it still abstracts, it still looks to structures and systems, it still generalizes. It just shows its work, is all.

In talking about containment, Sofia is also interested in dynamics of reserve and supply. Recent work in infrastructure and logistics has illustrated the deep implications of the global supply chain for the experience of everyday life in the so-called developed world. For example, Deborah Cowan has written about the “deadly life of logistics”—intensely militarized zones that protect and promote the speed and efficiency of global trade. These global “seams” are stitched out of private armies and deregulated labor zones— but at the end point of the supply chain, the home, they are precisely unobtrusive, invisibly facilitating every seamless online purchase. Last month, I wrote about the blood-soaked implications of those logistics in my own home:

“Every time they [my kids] pick up their devices they touch the hands of other, distant children set to work mining the rare earth minerals without which those screens would be lifeless. Every stitch of clothing I’ve ever put on their backs was made by some woman hunched over a sewing machine in a distant sweatshop, her baby laid on a blanket at her feet. Every morsel that ever nourished them was also freighted with the complex horrors of our food supply chain to animals, earth, and humans alike.”

This, too, is a technics of the unobtrusive. Its stakes are environmental as well as humanitarian. So this is what my book will do: turn a technics of the unobtrusive on the space of the home so as to disrupt its seeming function as a container only of that which is good, safe, secure and nurturing. I’ve already spoken (again, last month) of the psychological cost of this version of the home and its place in the world. But I also want to think about the more material costs. About how my home’s security is dependent, quite literally, on the precarity of another.

The question left dangling is about nature. Is it in the nature of supply, just as it is in the nature of gestation, to remain private, unobtrusive, unknown? That may well be. Certainly I cannot use my eyes to grasp the global supply chain, just as I couldn’t look at a pregnant person and understand what they are feeling as they do the work of gestation. I’d be required to use some other sense, some non-archimedian kind of imagination that grands authority to that which is precisely unseen. This I take to be the deepest meaning of a technics of the unobtrusive— a procedure of thought that gives equal theoretical weight to what cannot be thought, or known, but which by imagination can be felt.

Literally, it’s the leap day!

Those two things happened pretty much simultaneously for me: I had my first child in my first year of my first academic job out of grad school. I will probably have a lot to say about this in the future, but here I’d just like to make note of the coincidence because employment and parenthood are kind of THE benchmarks of adulthood and they hit me, in all their disillusioning force, right at the same time.

Statistically likely but not, in my case, an issue— and you KNOW I would tell you if I did. One of the small perks of having major abdominal surgery instead of giving birth vaginally is that it tends not to mess up your pee situation.

This is my translation of a common Spanish idiom for pregnancy, “la dulce espera.” As if one were not doing any work at all besides physically containing the miracle within, and tenderly, sweetly awaiting its outcome.

No one but fellow humanities U of C people ever get this but— I feel like when I showed up to college I was given like, a card or a cheat sheet with everything I now needed believe, or pretend I believed, in order to fit in there. A credo if you will: 1. Kant was wrong 2. Science is culture.

I’m not really sure why Kant was wrong, and in later years I’ve become very fond of what I can understand of that uptight lil guy— but I think upon reflection his wrongness may have been related to his status as an enlightenment thinker who believed in Reason and things like that. But the second credo I really took to heart!

Benjamin also used this metaphor of the mosaic to describe modes of thinking.

Andrea Krauß, “Constellations: A Brief Introduction” trans. James McFarland. MLN 26 (2011): 439.

This is an idea that I got from Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition but which obviously comes from Greek philosophy, specifically Archimedes, who at one point allegedly remarked if he had a fulcrum and a lever long enough, he could lift the earth. The critique of this idea is essentially, what does it serve thought or practice to speculate on something that cannot exist? The “archemedian point,” then, is that imaginary perspective of thought or reason that allows an inhuman, abstracted position from which one could get an “objective” or true picture of an outside reality. It’s the position taken by most enlightenment thinkers vis-a-vis society, the mind, etc. and is thus a primary source of critique from feminists and others who are interested in the body and, more precisely, in naming what that so-called universalism excludes (viz women, queers, and racial others to start).

Also my favorite book of all time! No wonder we get along. (I was not that sick, but I spent my whole pregnancy only feeling good in water, which is inconvenient when one has other things to do, such as work.)

You undboutedly know about Shulamith Firestone's artificial womb thing, but I'll mention it on the unlikely chance you don't.

Kant is so irritating.

I think of the gestating womb as the opposite of unobtrusive. Mine made itself known to me and then others in such assertive ways, including jutting out so far as to look precarious.

I also think that to treat the womb as a distinct vessel from the woman herself is to give credence to the idea that it can be independently legislated. Most women might prefer less focus on our wombs; that might allow us more holistic participation in our cultural life.